| Nine ladies dancing |

I have already discussed the interesting story of "dance", but what about "lady", a word obviously close to my heart?

It is derived from an Old English word, hlæfdie, a compound of hlæf (bread) and dige (kneader). From its earliest appearance in written records, this "bread kneader" was the woman in charge of a household.

The second element of the compound, dige, is related to the word that gave us "dairy", as we saw in our last post. The first element, hlæf, evolved into "loaf", its place as the collective word for the staff of life usurped by "bread", which started out meaning "a piece of food". "Give us today our daily loaf" and "I am the loaf of life," said Anglo-Saxon Gospel translations.

When I first started my word history segments on CBC Radio, there was much agonizing among the producers as to whether it was ok for the host to call me "the Word Lady" or if in fact this was sexist. Should it be "Word Woman" instead, they wondered (well, some of them suggested that "Word Wench" had a nice ring to it). To me, "Word Woman" had connotations of superhero(ine?) about it. After looking into it, I decided that any hesitation I had about "Word Lady" was due to its association in my mind with compounds like "tea lady"and "cleaning lady", and that I should just get over myself. So, Word Lady I am. If "lady" is good enough for the Virgin Mary, it should be good enough for me, I figure.

P.S.

If you find the English language fascinating, you might enjoy regular

updates about English usage and word origins from Wordlady. Receive

every new post delivered right to your inbox! You can either:

use

the subscribe window at the top of this page

(if

you are reading this on a mobile device): send me an email with the subject line SUBSCRIBE to

wordlady.barber@gmail.com

Privacy

policy: we will not sell, rent, or give your name or address to

anyone. You can unsubscribe at any point.

Follow

me on twitter: @thewordlady

For what swans have to do with singing, click here:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-swans-swimming.html

For what swans have to do with singing, click here:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-swans-swimming.html

Why we don't say "gooses" and "gooselings:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-geese-laying.html

For why we don't say "fiveth", "fiveteen", and "fivety", click here:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-fifth-day.html

For why it was OK to call the Virgin Mary a "bird", click here:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-calling-birds.html

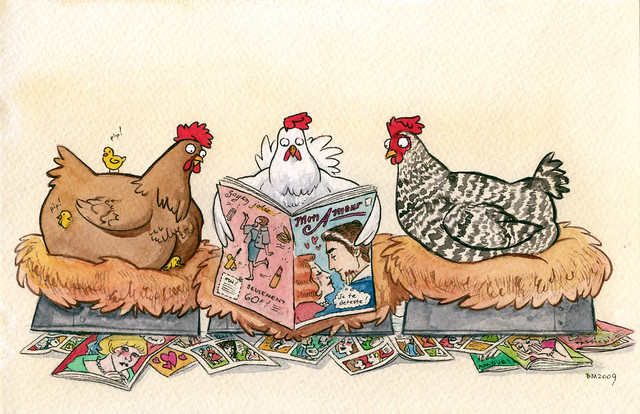

For what French hens have to do with syphilis, click here:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-french-hens.html

For turtle-doves, click here: http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2014/12/12-days-of-wordlady-turtle-doves.html

For what partridges have to do with farting, click here:

http://katherinebarber.blogspot.ca/2013/12/12-days-of-wordlady-partridge.html